Call for Army Reforms-Nehru’s Idea

On September 12, 1946, soon after taking oath as Foreign Minister in the pre-independence Indian Cabinet, Jawaharlal Nehru sent a letter to the Commander-in-Chief and Defense Minister urging comprehensive reforms in the Indian Army. According to Nehru, these reforms were necessary to protect the soon-to-be Independent India.

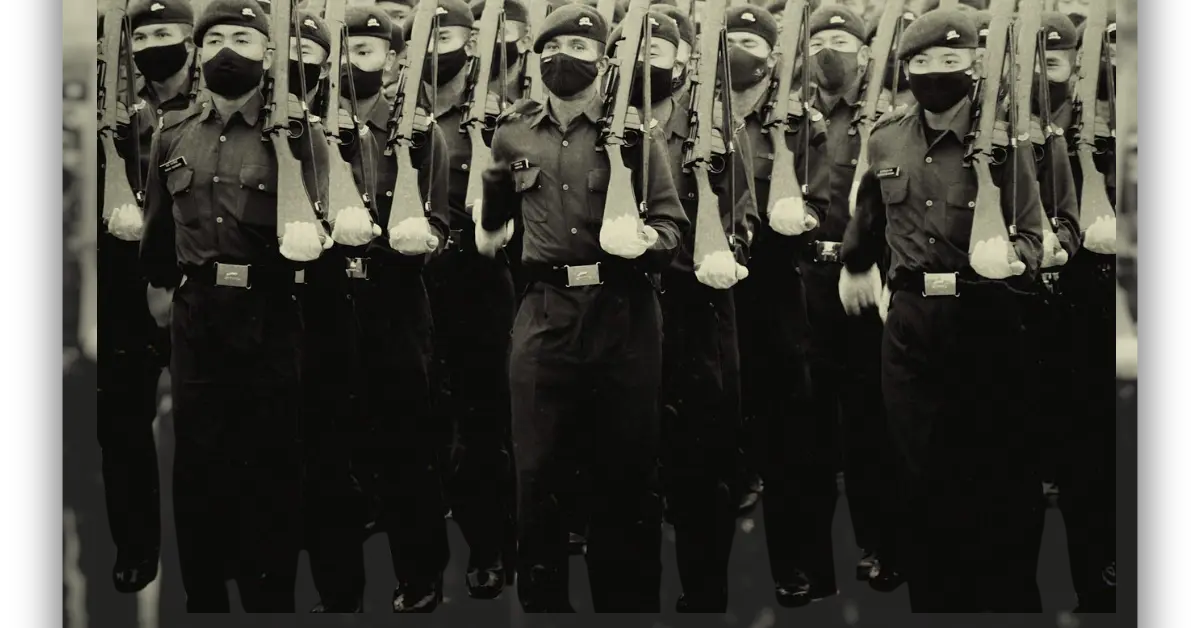

According to Nehru, the need of the hour was to “change the entire history of the Indian Army,” they felt the need to modify its composition based on fighting classes heavily recruited from Punjab and other areas. Instead, there was a need to open up the army in a way that reflected the aspirations of the Indian nation as a whole.

The Congress Party had for years criticized the colonial policy of recruitment in the Indian army based on caste and community. The divide-and-rule policy that the Britishers adopted post-1857 revolt had to end, as they now had precise control over the country.

However, reforming the army was difficult, especially in the delicate years after Independence. Continuing instability in various parts of the country, like the war with Pakistan and military action in Hyderabad (Operation Polo), has made the stability of the Army imperative.

Perhaps the most significant obstacle came from the senior officer corps, who felt that mixed recruitment could make it challenging to control discipline in the Army and may face opposition to a change.

In subsequent years, although some mixed regiments were formed, the infantry remained largely caste and community-based. Currently, there are 27 class regiments in the Indian Army. The Agnipath Scheme, announced by the Indian government, aims to transform class-based military recruitment and open it up to an ‘All-India, All-class’ basis.

While caste- and community-based recruitment is seen as divisive on the one hand, experts and senior army officers point to the historical context in which the system emerged and say a change could affect the sense of brotherhood that is essential to the correct functioning of the system.

Colonial Policy

When the British arrived in India, they discovered they did not have enough white labor to consolidate their rule over a foreign country. There were two reasons for this.

Firstly, European forces would cost more, and secondly, the Indian climate would be too harsh for the white soldiers, and most of them would want to leave too soon. In this sense, it was preferable to recruit Indians because they were more accustomed to the geographic and social landscape and were more easily accessible for work

However, the reason why Indians were willing to fight in the British army is a question that researchers have been trying to understand for years. Military historian Kaushik Roy points out in his article “Regiment Building in the Indian Army: 1859-1913” (2001) that “management skills were the main factor that enabled the British to build an army that was loyal and effective in combat.”

Since nationalism could not be used to foster regimental pride, British officers motivated the sepoys of the Bengal Army before 1857 based on ideas of caste. The Brahmins and Rajputs were especially favored, and no lower castes were recruited to please them. Roy writes in his work that in 1852, 70 percent of the Bengal army was composed of Purbiyas, or the upper castes from Northern India.

However, things changed after the rebellion of 1857, in which the Purbiya units of the Bengal Army played an important role.

Studies on Eugenics began in Europe in the second half of the 19th century which became quite popular later on which talked about racial improvement British officers in India recognized that race, not caste, should be the basis for determining the characteristics of communities.

The martial race theory subsequently shaped the recruitment policy of the Indian Army. He assumed that only specific communities in the subcontinent could bear arms due to their biological and cultural superiority.

Lord Roberts, Commander-in-Chief of the Indian Army in the 19th century, stated that the fighting races in India were the Sikhs, Dogras, Gurkhas, Rajputs, and Pathans. “Small farmers and wheat-consuming communities in the cold border areas were seen as belligerent,” Roy wrote in a 2013 article in the journal Modern Asian Studies. The Gurkhas and Sikhs fought against the British in the Anglo-Nepalese War of 1814 and the Anglo-Sikh Wars.

Therefore, the British knew their military strength and wanted to recruit them. Through the Treaty of Sugauli in 1816, Britishers started recruiting Gorkhas From Nepal after seeing their prowess. The Gorkhas comprised one-sixth of the British Indian Army by the First World War.

It is important to note that class regiments, in the British sense, did not consist of a single caste category but rather a combination of different caste groups. For example, the Dogras were made up of several different castes from Jammu, Punjab, and Himachal Pradesh, the Gorkhas included several other groups from eastern and western Nepal, and the Kumaonis referred to several hill castes from the Uttarakhand region.

Additionally, different regiments were allowed and encouraged to wear different uniforms to maintain a distinct identity and increase the prestige of each unit.

The 1st Punjab Cavalry, for example, wore a dark blue uniform with blue and scarlet pagris (turbans). Their badges were engraved with “Delhi” and “Lucknow” to commemorate their loyal conduct during the 1857 rebellion.

An army for an independent India

The military’s dependence on a few regions and communities became a concern during World War I when demand for troops increased. Although the British opted for broader recruitment during this period, those recruited from non-belligerent areas primarily performed support roles rather than as front-line combatants.

After the war ended in 1918, regiments recruited from outside privileged groups (such as the Bengal detachment that had served in Mesopotamia) were quickly disbanded because they had not performed well.

However, as independence approached, the highly unbalanced nature of the colonial army was seen as increasingly unsuitable for a democratic country. The most widespread argument was the injustice of a system in which several municipalities and regions had to pay taxes to maintain an army from which they were excluded.

Things changed after 1947, when many British regiments left the Indian Army, and most Muslim regiments were transferred to Pakistan, requiring significant adjustments.

However, while political instability in India and territorial conflicts with neighboring regions represented a significant obstacle to reforming the system, restructuring the army became even more difficult for most politicians, including Nehru; the immediate objective after independence was to reduce spending on the Army.

However, the most significant opposition to reform came from senior army officers, particularly at a time when it was possible that India would soon go to war with Pakistan.

The views of the first Commander-in-Chief, General KM Cariappa, are a good example of the top leadership’s commitment to the class regiment system. “As a brigadier and the only Indian officer to serve on the Indian Army Reorganization Committee in 1944-45, he was far from opposing the class regiment policy but instead lobbied for the conversion of the five proposed mixed regiments as class regiments only after 1945 to increase its military effectiveness,” writes Wilkinson.

Other senior officials shared similar views. General K. S. Thimayya, who served as Chief of the Army Staff from 1957 to 1961, suggested that “soldiers perform better when their units are not mixed.

Lieutenant General JS Cheema, as Deputy Chief of Staff of the Sikh Regiment, explains that the majority of the Indian Army is made up of village men. “For them, the affinity that comes from being from the same region or having the same language, religion, and culture becomes a powerful motivator.”

The feeling of camaraderie and brotherhood that develops within battalions plays a vital role in mutual protection in combat.

Jaswal recalls an incident during the Indo-Pak war in 1965. “There were two soldiers from a village in Himachal who practically ate from the same plate. As the war progressed, one of them was shot and abandoned in a stream. The other one ran back from where he was supposed to go to pick him up and bring him back immediately,” he says. “The reason was that if he left his friend behind, it would be impossible for him to face his relatives in the town. He would be excluded.

A similar example of bonhomie is cited in the Battle of Rezang-La during the Sino-Indian War of 1962. The Ahirs of Haryana, who fought in the 13th Kumaon Regiment, are known to have bravely repulsed repeated attacks by the Chinese during this historic battle. “They were practically all from the same town and had family ties between them. Brothers, fathers, and sons fought together in the same trench,” says Jaswal. He added, “Courage increases exponentially when the combatants belong to the same region.

Case of president body guard

The President’s bodyguard, formed in 1773, is taken from three caste regiments: Hindu Jaat, Jaat Sikh, and Rajput.

It remained for many years as one of the oldest military cavalry regiments in the world, consisting of horses.

They are recruited from these castes because of functional requirements, as stated by the Indian Army during the SC hearing 2019, as many Presidential ceremonies demand good height, build, and Appearance.

Chamar regiment

The Chamar regiment was founded during WW2 with its headquarters in Jabalpur but was later disbanded in 1946 as it was said that they went against the British army and joined the INA of S.C. Bose.

But later on, some jawans from the regiment revolted against the decision to disband it, and 46 of them were arrested.

Recently the Bhim Army Chief Chandrashekar Azad has reiterated its demand for reinstating the Chamar regiment in Parliament in 2024.It was also supported by the National Commission for Scheduled Castes who written a letter to then defence minister Manohar Parrikar as few years back when some veterans who served in Chamar regiment called for its revival.

But after independence, no such regiments were disbanded nor formed.